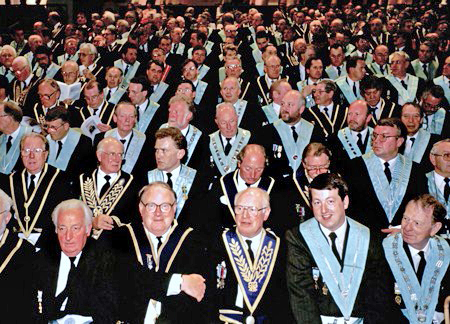

FRANÇOIS PÉROL, the adviser whom Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s president, controversially appointed in February to head two merging mutual banks, is not known as a champion of transparency. But Mr Pérol has let it be known that he intends to reduce the influence of freemasons at Caisse d’Epargne and Banque Populaire. He has refused an invitation to a tenue blanche ouverte, a masonic meeting that non-freemasons may attend. And he does not want senior posts shared among the banks’ various rival lodges.

French business may be particularly full of networks, but every country has its cliques, whether based on education, social background or spiritual beliefs. In Spain, Italy and Latin America as well as France, businesspeople speak of the influence of Opus Dei, a conservative Catholic lay order which supports a number of business schools. America has its Ivy League alumni groups and Rotary clubs. Chinese businesspeople often rely on guanxi, or personal connections.

At the same time online professional networks such as LinkedIn, headquartered in California, Viadeo, a French-owned website, and Xing, a site with a strong presence in German-speaking countries (formerly called OPEN Business Club), are surging in popularity, thanks in part to fear of lay-offs amid the recession. A year ago it took LinkedIn over a month to win 1m new members; it now takes about 15 days and the site has 42m members around the world. Online networks, in contrast to the old kind, are open to all and easy to join.

Old-style networks, however, are usually stronger than online ones, and the trust between their members facilitates transactions of all sorts. They can be particularly helpful for young companies in emerging markets. A study of entrepreneurship in China by Yusheng Peng of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, for instance, showed how kinship networks helped firms protect their property, obtain reliable information and identify opportunities. Social networks can also be speedier than formal systems: in July 2002, for example, when Vivendi, a French conglomerate, was weighed down with debt and needed to raise €3 billion (then $3 billion) in three days, its chief executive at the time, Jean-René Fourtou, turned to a group of bosses who were fellow rugby fans, including Claude Bébéar, then the chairman of the AXA Group, an insurance firm, and the money was secured.

Some old-style networks aim to bring an ethical dimension to business. Not all students at IESE, a leading business school with campuses in Barcelona and Madrid, are aware that it is “an initiative” of Opus Dei. But many of them, particularly those of Spanish origin, are invited to join the order, says one graduate who was approached during his time there. IESE has a network of 15 business schools in developing countries, some of which explicitly state a goal of bringing a Christian perspective to business. Combining family with work, for instance, is the special subject of Nuria Chinchilla, a professor at IESE.

But networks can also have baleful effects. They sometimes abet crimes. At French firms there is often pressure to hire or promote people based on their connections, businesspeople say. A study by Francis Kramarz and David Thesmar published in 2006 by the Institute for the Study of Labour in Bonn looked at three French business networks: former civil servants who graduated from the École Nationale d’Administration, former civil servants who graduated from the École Polytechnique and École Polytechnique graduates who went straight into business. These two elite schools, which produce 500 or so French graduates a year, dominate the boards of France’s biggest companies. The study showed that firms run by former civil servants who maintained their links to government markedly underperformed those run by executives with purely private-sector backgrounds.

Competition suffers, too. Nicolas Véron of Bruegel, a think-tank, says networks make it hard for new firms to emerge in France, since established ones are conservative about whom they do business with. As a result, he says, “you often see that successful young firms are business-to-consumer rather than business-to-business.”

On the face of it, networks are less important in more meritocratic America. Only 11% of bosses at big American firms received their undergraduate degrees from an Ivy League college, according to a survey last year by Spencer Stuart, an executive search firm. That suggests that performance matters more than the old school tie. But a 2007 study of mutual funds by Lauren Cohen and Christopher Malloy of Harvard University and Andrea Frazzini of the University of Chicago found that American fund managers invested more money in firms run by people who attended the same university as them. Moreover, membership of Rotary “service” clubs, which started in Chicago in 1905 and have since spread across the world, is by invitation only, and women were not admitted until the late 1980s. The Lions Club International, also based near Chicago, may be the most global offline business network, with 1.3m members in more than 200 countries. A third business network is the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, members of which must be Christians.

Will technology and globalisation undermine old networks? In some cases they are weakening. Swiss banks’ hierarchies, for instance, used to bear a resemblance to those of the country’s army, with strong connections between the two. But the network has largely disappeared, thanks to globalisation and a decline in the army’s role in society, says a Swiss banker. Guanxi are different from Western networks: they are much more personal, informal and subtle. Their importance is also diminishing as the Chinese economy becomes more market-oriented, says Derek Ling, founder of Tianji.com, a networking site owned by Viadeo.

“An active, open online network is far more competitive in today’s globalised business environment than local, closed networks such as alumni groups or freemasonry,” argues Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn. Online networks’ most compelling advantage, in addition to openness and efficiency, is the chance they offer to connect across borders and among different sorts of people. Traditional networks, by contrast, tend to be strongest in domestic industries, such as construction. About two-fifths of LinkedIn’s members are female, whereas offline networks are usually dominated by men. And online networks include more entrepreneurs than traditional groups: they make up 30% of Viadeo’s subscribers, according to Dan Serfaty, the website’s co-founder.

Nevertheless, the old structures will not fall away soon. Indeed, Mr Serfaty argues that online networks can reinforce offline ones. A graduate of HEC (École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Paris) might use the school’s own website to look for any alumni working at, say, Google, he says. But using Viadeo’s tools, he can also do a broader search for anyone who attended HEC and knows someone working at Google, so the network becomes more powerful. Online networks make it easier to gather information on firms and their employees, argues Jean-Michel Caye, a specialist in human resources for the Boston Consulting Group in Paris. But if you want to influence a big decision or secure a job, he says, “it’s still the old networks that really count.”