Origins

Agreeing on the precise origins of Freemasonry is no easy task. Because of a sense of discretion and word-of-mouth transmission of the tradition over the centuries, reliable historical sources are few. Yet this fundamental attachment to tradition has given rise to a great many legends and the spread of a somewhat mythical history. Thus, some sources would have us see Adam as the first Freemason and the history of the institution as that of the history of the universe itself, using a chronology of the Bible which dated the Creation at 4,000 years BC, but this kind of idea has led many who are interested in the subject to confuse history with legend.

Even if Freemasons rightly seek to carefully preserve the symbolic nature of rituals whose origins largely lie in myth and legend, the historical narrative of the institution itself needs to be fairly rigorously set straight. It is nonetheless true that some paths of descent claimed by Freemasons, even if historically open to doubt, preserve a rich spiritual and psychological meaning in that they express a willingness to keep to a tradition hat is at the heart of mankind’s heritage.

If fact, if the earliest history of the Order is far too vague for the purposes of historical review, that of the events of the past three centuries can usefully be applied to historical scrutiny.

Modern Freemasonry has undeniably links with the mediaeval guild systems of the stonemasons and quarrymen who built religious and civil buildings. We know in particular that the mediaeval cathedral builders of the Gothic cathedrals were formed into lodges and were subsequently referred to as operative masons, whose Patron Saint was St. John.

The origin and development of the Masonic Order are to be found in the British Isles: modern or “speculative” Freemasonry started to emerge in London towards the end of the 17th Century and became officially set up in the first quarter of the 18th.

The term ‘free mason’ (franc-maçon in French) first occurs from around 1376, but its exact meaning at the time is uncertain. According to some, it refers to a craftsman exempted from taxes and other feudal obligations, thanks to a privilege similar to that granted in those days to the franc métiers of France.

According to others, a free mason was a freestone mason, a Craftsman skilled in working freestone, the high quality stone used in the more finely worked parts of a building, as opposed to the rough mason or quarryman who worked the rough stone usually used for the underlying structural parts.

These mediaeval operative masons in Britain were, like their Continental counterparts, travelling craftsmen moving from one site to another. Thus they differed from craftsmen settled in the towns and new boroughs and this might have prevented their professional organisations from developing in the same way as the urban guilds.

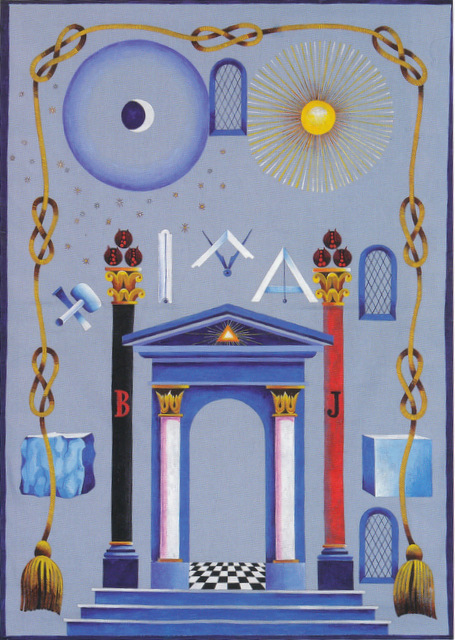

On site, masons met in a Lodge, both a workplace and a living space, first mentioned as far back as 1277. There they worked under the Master of Works, or “Master of the Lodge”. Apprenticeship was long and difficult. It took seven years before an apprentice was entered in the Lodge’s register and just as long before he was accepted as a “Fellow of the Craft”, in other words a qualified craftsman and master of his art – and of his fate, for once he had been given certain secrets (based on a legendary account of Salomon’s temple) he could travel throughout the land in search of work.

English Lodges possessed a manuscript setting out the rules of the Craft, the Old Charges, which were read out solemnly during certain occasions. They began with a prayer to the Holy Trinity, related the legendary history of Freemasonry and ended by listing its moral and professional ideals; in short a true professional code. The legendary history describes the origin and the development of the art of building from earliest times, with particular attention to King Solomon’s Temple.

Two ceremonies, that of communicating the ‘Mason Word’ in Scotland and the reading of the Old Charges in England, are the only precise indications of ritual work in the Lodges of the period and in this sense they are the first steps towards the rituals of today. Based on the existence of this first spark of a spiritual message, it seems reasonable to deduce that within these closed groups of men, bound together by a daily practice of their craft and their shared secrets, there soon arose the feeling found in every initiatory society: that of brotherly affection linked to a two-fold duty to improve oneself materially, professionally and spiritually, as well as to help one’s fellows improve themselves. Nothing else could really explain the transformation that would later occur with what was to become known as the ‘Acception’.

In the 17th and 18th Centuries, the way the craft operated changed radically. The disappearance of traditional workshops near cathedrals, abbeys, castles and so forth, led to craftsmen settling permanently in towns. This effect gave rise to what became in effect powerful and well-organised Guilds, soon taking part in the governance of their local communities. This was the case in London in particular, where the old types of operative lodge were quickly overtaken by the social and economic revolution. Largely deprived of their authority over the craft, they would have died out completely had it not been for outsiders seeking to join from the cultivated, well-off middle and upper classes. We find these ‘Accepted Masons’ from the first half of the 17th Century and their numbers were to grow until the first years of the next century.

Even if we know little of the motives drawing these men to workers’ organisations in decline, we can imagine that they were moved by a conviction, or at least a hope, that they would find in the Lodges not so much a craft skill of little use to them but enrichment of a spiritual kind. That is the only possible explanation of this phenomenon which was to shape the face of modern Freemasonry. During the course of the 18th Century, the Lodges, till then temporary organisations for regulating the craft, providing mutual aid and professional training, became a brotherhood aimed at spreading an undefined spirituality and ethic, veiled in symbol and illustrated by allegory. The mason’s tools, the very stone he worked, became a symbolic support for metaphysical and moral reflection.

This was a real revolution, an almost root and branch break with the past, with enormous consequences. These new men, Accepted Masons, brought into an age-old institution the moral; religious and philosophical preoccupations of their time.

From this fortunate coming together came modern Freemasonry, which came about officially when four London Lodges amalgamated on 17 June 1717 to turn what had been referred to as “that most Ancient and Right Worshipful Fraternity” into a body which soon came to be called the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster and afterwards the Grand Lodge of England. Its Constitution was published in 1723, the work of Dr. James Anderson, a Presbyterian minister. In fact it was mostly the operative “Old Charges” re-compiled. However, his Constitution marked a turning-point: whereas the old documents were purely Christian in nature, this Constitution clearly affirmed a principle of religious tolerance in a respect for all faiths.

From then on Freemasonry spread rapidly throughout Great Britain, Europe and the Americas. In the 18th Century appeared the final setting down of the customs and rituals observed throughout the English-speaking world to this day, without detracting from the fundamental principles of 1723: belief in God, the brotherhood of man through respect for another’s conviction and faith, respect for the lawful civil authorities, refusal to accept women within the Order and abstention from any interference in political and religious affairs. The historical importance of this last principle cannot be stressed heavily enough. Its being called into question, then abandoned in some countries, gave rise to irregular freemasonry as a fundamental deviation from the original institution.

The Freemasons of the early 18th Century were very conscious of the fact that, though drawn together by a common aspiration and mutual affection, they had divergent, if not divisive, approaches to both religious and political issues. Firstly, as to religion, English Lodges in 1723 included Anglicans, Catholics, Non-conformists and also non-churchgoing deists among their number and were virtually open, in terms of their principles, to the other religious groups that were later to provide them with members, Jews, then Moslems, Hindus and so on. In terms of politics also, since conservative and liberal persuasions were taking shape and the successive predominance of Roman Catholics and Protestants had also posed a political problem.

From the start it had been considered essential that Brethren should be able to meet in peace in the name of everything they held common; and that whatever might divide them socially should be kept decidedly outside the Lodge.

Over the centuries, strict application of these principles has guaranteed Freemasonry’s harmonious and peaceful development throughout the world. One or two exceptions, in some Latin countries, have demonstrated the excellence of this rule ab absurdo.

R.L. La Constante Fidélité, nr 19 – O. Mechelen